Home » Works

Category Archives: Works

Polish Political Platos in Brill’s Companion

Brill’s Companion to the Legacy of Greek Political Thought edited by David Carter, Rachel Foxley, and Liz Sawyer is one of the latest volumes in the series (vol. 8, Leiden-Boston 2024). Contributors to this volume investigated a range of responses to issues surrounding the legacy of Greek political thought, exploring the ways in which political thinking has evolved from antiquity to the present day.

One of the chapters in this book was authored by Tomasz Mróz who discussed variety of Polish interpretations of Plato’s political works in studies written by nineteenth-century Polish authors (Plato’s Political Works in Nineteenth-Century Polish Thought, pp. 335-363), including historians of philosophy, philosophers and social thinkers. Their diverse views on the Republic of Plato reflected the wealth of ideas which are present in Plato’s opus. In spite of their various intellectual backgrounds and goals, all these authors found inspiration in Plato’s work for the implementation of his political ideas into their own arguments touching upon contemporary social or political issues, including the questions of democracy, socialism and gender equality.

Let’s say a few words about the authors presented in Mróz’s chapter to give a glance of its content: Bolesław Limanowski (1835-1935), a socialist thinker, regarder Plato as a progressive philosopher, despite his disregard for democracy. For Wojciech Dzieduszycki (1848-1909), a conservative politician, Plato’s socialist and feminist ideas were too destructive for society to be implemented. Wincenty Lutosławski (1863-1954), a famous Plato scholar, considered Plato’s socialism as a natural consequence of his metaphysics and only a transitional step in his development. Stefan Pawlicki (1839-1916), a neo-Scholastic philosopher, claimed that even Plato’s most controversial political ideas (communism and feminism) had stemmed from his deep moral beliefs, but all their shortcomings were later to be corrected by Christianity. Eventually, Eugeniusz Jarra (1881-1973), a historian of legal philosophy, emphasised gender equality and the possibility of social promotion as progressive ideas supporting democracy.

PS.: this chapter was edited and improved by Una Maclean-Hańćkowiak and is presented on Kudos platform.

H. Jakubanis’ Empedocles in OA

Last year we announced publishing Polish translation of a Russian study by Henryk Jakubanis (1879-1949), originally published in Kyiv over a century ago, Empedocles: a Philosopher, a Doctor and a Magus, therefore there is no need to repeat all the information here. Suffice to say that the text was translated by Mariam Sargsyan and Adrian Habura, and the whole volume ends with an afterword by Katarzyna Kołakowska, a contemporary Polish expert on Empedocles.

The book can be purchased on the publisher’s website here. We are now, however, glad to inform that it is available in OA, via online repository of the University of Zielona Góra.

Henryk Jakubanis and His Kyiv Years

Henryk Jakubanis (1879-1949), his life and intellectual legacy, have been in recent years the topic of research pursued by Mariam Sargsyan. In one of her papers, titled Henryka Jakubanisa (1879-1949) kijowski okres życia i twórczości historycznofilozoficznej (H. Jakubanis’ Kyiv Period of Life and Work in the History of Philosophy), she presented Jakubanis’ Kyiv years as fundamental and formative period of his intellectual biography. Her study has been published in Polish and can be downloaded here.

Kyiv period of Jakubanis’ life deserved a separate presentation, because our knowledge of his early career was far from satisfactory, not to mention some inaccurate or even false informations. M. Sargsyan was the first researcher who used Jakubanis’ documents from the University Library of the Catholic University of Lublin to such an extent, what was necessary to complete her task.

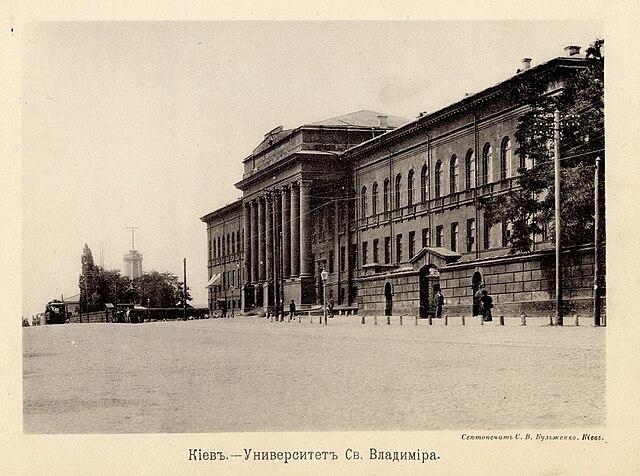

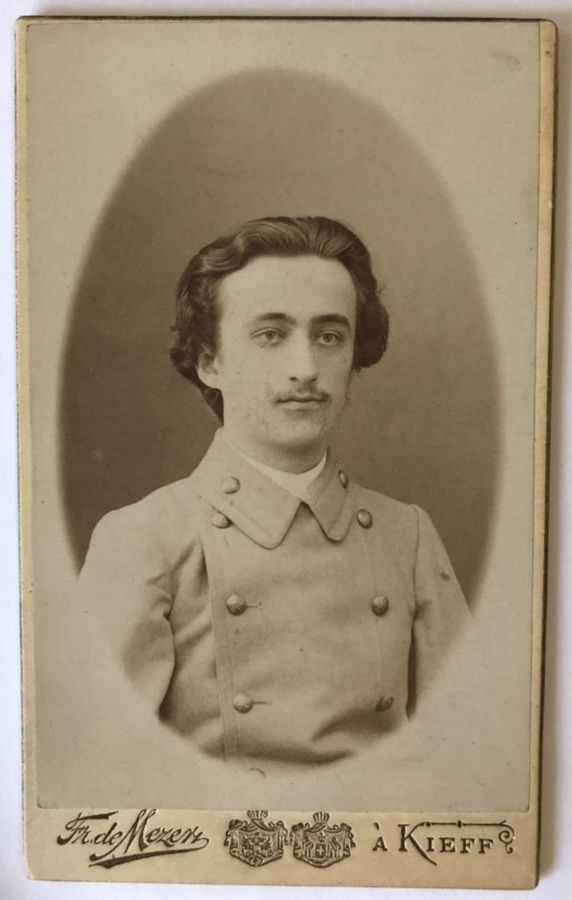

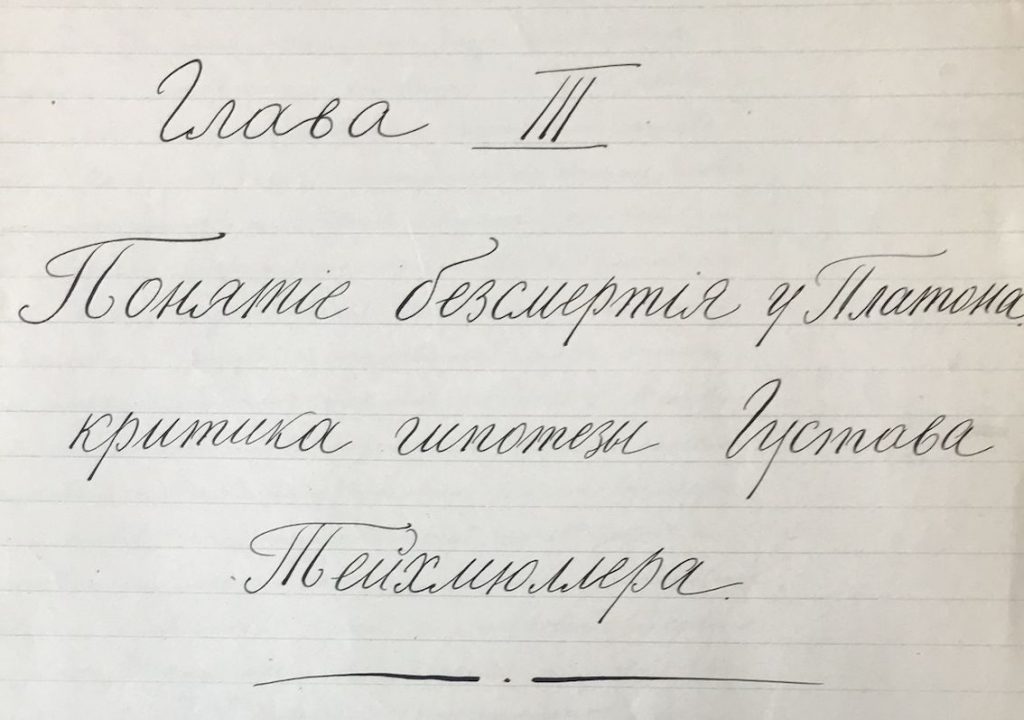

To present the life and academic activity of Jakubanis (on the right) in the Kyiv period in full, Sargsyan starts with his childhood and gymnasium education. Moreover, the history and philosophical traditions in the Saint Vladimir Imperial University of Kyiv are briefly sketched with an emphasis on Jakubanis’ study curriculum, the beginnings of his academic career and the personality of his supervisor, professor Alexei Gilarov. He was the professor who exerted the most significant impact on Jakubanis’ early works in the history of Greek philosophy.

To conclude, it was in Kyiv where Jakubanis’ career as a teacher of classics and a researcher in the history of ancient philosophy started. Some of his achievements from this period are still of significance in the Russian-speaking world, for he is still remembered as the author of a work on Empedocles and one of the pioneers in translating fragments of this ancient thinker into Russian.

A Biographical Sketch on Henryk Jakubanis

Mariam Sargsyan, an AΦR researcher focusing on the legacy of H. Jakubanis, has recently published a paper Henryk Jakubanis (1879–1949) – a Historian of Greek Philosophy Between Kyiv and Lublin, which aims at discussing the entire academic path of this researcher of ancient philosophy, presenting his work in both periods of his life, connected to Kyiv and Lublin. The paper was published in Polish and can be downloaded here.

It is not insignificant to remark that Sargsyan’s paper has been published in an issue devoted to classical philology of “Roczniki Humanistyczne” (“Annals of Arts”, Vol. 72 No. 3, 2024, pp. 79-97), a journal edited at the Catholic University of Lublin (KUL), where Jakubanis used to work for over two decades of his life.

Jakubanis’ life began in the Russian Empire, and Sargsyan presents his family and his initial education it the gymnasium, with a focus on classical languages and humanities. Then the story proceeds to the Kyiv period of his life, including a brief sketch of the history of St Vladimir’s Imperial University of Kyiv and the researchers of the history of philosophy there, with an emphasis on Jakubanis’ academic supervisor, Alexei Gilarov (1856-1938). During his Kyiv period Jakubanis won a scholarship for a study visit in Germany, notably in Berlin, and was active as a university lecturer, teacher at various courses extra muros, and started to develop his academic and research career.

The Lublin period began in 1922 with Jakubanis’ repatriation from the then Soviet Ukraine to Lublin in the independent Republic of Poland. Thanks to the support of Tadeusz Zieliński (1859-1944), his former examiner in Kyiv, Jakubanis was hired at the University of Lublin. His lectures and seminars there, his life during the war, his works and impact are further discussed in the paper.

To sum up: Jakubanis spent 26 years of his life in Kyiv and 27 in Lublin where he died in 1949. These two periods were almost equal in terms of time, yet they were quite different. In Kyiv he composed most of his works and was formed as a researcher and teacher in classics in general and in the history of ancient philosophy in particular, while in Lublin he was rather occupied with university life and lecturing, and it did not allow him to focus on researching and publishing. For his entire life, however, he remained faithful to his interests in ancient philosophy and, according to his students, spared no energy to disseminate his knowledge and expierience in this field.

AΦR at the 3rd Congress on Polish Philosophy

The 3rd Congress on Polish Philosophy took place in October (18th-20th) in the Rydzyna Palace. It gathered scholars interested in researching the tradition of Polish philosophy and developing it. Two members of the Ancient Φilosophy Reception research group took part in this philosophical event: Adrian Habura – online, and Tomasz Mróz – onsite. The first of them spoke about the concept of love in the works of Władysław Tatarkiewicz (1886-1980), while the latter – on the history of studies on the reception of ancient philosophy in Poland.

Mróz’s paper was directly concerned with problems related to the reception of ancient philosophy and started with quotes of diverse opinions of two eminent Polish researchers in the history of Greek philosophy, that is, Stefan Pawlicki (1839-1916) and Wincenty Lutosławski (1863-1954). Lutosławski, when composing his works on Plato, searched for Polish authors and their studies to provide references to them, while Pawlicki paid no interest to the works of his compatriots on Greek philosophy.

In more recent decades it was Izydora Dąmbska (1904-1983), a philosopher and historian of philosophy, who published a study on the reception of Plato in Poland (1972), but nowadays many books and papers on this topic were published by the members of the AΦR research group. Concluding his talk Mróz briefly presented research projects of the members of the AΦR and the books they had published, to start with the latest one:

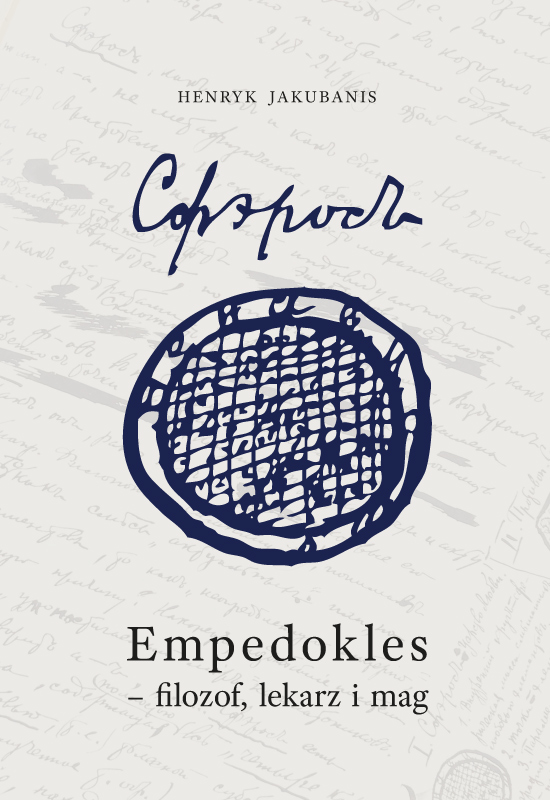

Henryk Jakubanis, Empedokles – filozof, lekarz i mag: Przyczynek do jego zrozumienia i oceny (Empedocles: a Philosopher, a Doctor and a Magus. Materials for Understanding and Assessing Him), transl. from Russian and ed. Mariam Sargsyan, A. Habura, Wydawnictwo Marek Derewiecki, Kęty 2024, 104 pp. (Studies and Texts in the History of Reception of Ancient Philosophy, vol. 3).

T. Mróz, Stanisław Lisiecki (1872-1960) i jego Platon (Stanisław Lisiecki (1872-1960) and His Plato), Wydawnictwo Marek Derewiecki, Kęty 2022, 150 pp. (Studies and Texts in the History of Reception of Ancient Philosophy, vol. 2).

T. Mróz, Plato in Poland 1800-1950: Types of Reception – Authors – Problems, Academia Verlag / Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden Baden 2021, 480 pp. (Academia Philosophical Studies, vol. 75).

S. Lisiecki, O Platonie, Arystotelesie i o sobie samym (On Plato, Aristotle and on Himself), ed. T. Mróz, Wydawnictwo Marek Derewiecki, Kęty 2021, 367 pp. (Studies and Texts in the History of Reception of Ancient Philosophy, vol. 1).

and some earlier ones…

Henryk Jakubanis and His Empedocles

Empedocles: a Philosopher, a Doctor and a Magus. Materials for Understanding and Assessing Him.

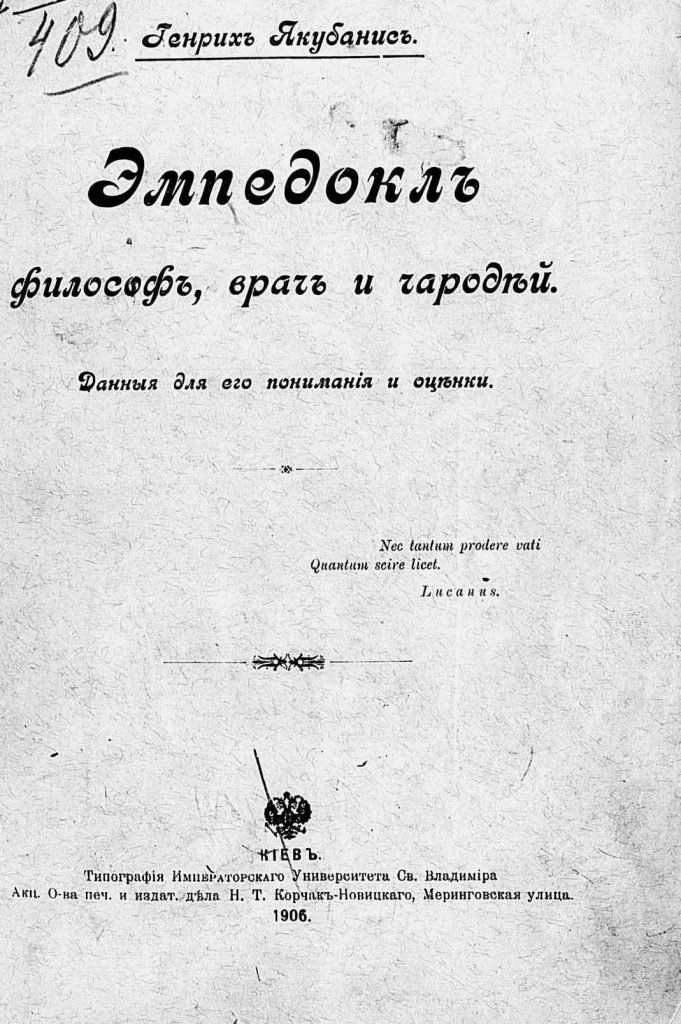

It was the title of the most important work by H. Jakubanis (1879-1949)

originally published in Kyiv in 1906.

At the time of publishing this book the author was a young, 27 years old, lecturer and researcher at the St. Vladimir Imperial University of Kyiv. His area of competence and interest was established, it was ancient literature and philosophy with an emphasis on Greek philosophers. This volume consisted of two main parts: 1) Introductory presentation of Empedocles’ life, Sicilian society, culture etc., and finally – the sources of his philosophical thought. 2) Translations of the remaining fragments of Empedocles in verse and prose, with philological commentaries. It is the Jakubanis’ translation of the philosopher’s texts that won him recognition in the Russian-speaking world. Suffice to say that it is still in circulation today.

Jakubanis’s Empedocles had to wait for over a century to become finally available to Polish reading audiences. Until now this work had only been listed in bibliographies with no hint regarding its content. Two young Ph.D. students and researchers of AΦR group, Mariam Sargsyan and Adrian Habura, took their time to translate it from pre-reform Russian into well readable contemporary Polish. With their introduction the book was published as volume 3 of the book series published by Marek Derewiecki. Naturally, only Jakubanis’ own text was translated into Polish, for there was no need to re-translate his Russian renderings of Greek philosophical poetry. All the more so that Polish readers have a complete translation of Empedocles’ fragments by Katarzyna Kołakowska, a researcher from Jakubanis’ beloved Catholic University of Lublin.

It should only be added that the book is accompanied by an afterword by Kołakowska and it is available on the publisher’s website here.

This book is one of the results of the research project funded by National Science Centre on Henryk Jakubanis (1879-1949) as a classics scholar and historian of ancient philosophy.

Plato in Poland book available in OA

This post is only to announce that the book by T. Mróz, Plato in Poland 1800-1950. Types of Reception – Authors – Problems (Academia Verlag/Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden Baden 2021), as a result of the agreement with the publisher, is now available free in open access on the Nomos Verlag website here and in the repository of the University of Zielona Góra, here. Enjoy!

Recent commentaries