Home » Posts tagged 'Totalitarianism'

Tag Archives: Totalitarianism

Neverending Story of… Plato in Poland

This time it was at the University of Hradec Králové where the word about Plato reception in Poland was spread. Tomasz Mróz, among his activities in accordance with Erasmus+ Teaching Assignment, delivered a talk on political aspects of Plato reception in Poland. The focus was, naturally, on Plato’s Republic and on the connections between the interpretations of Plato’s political philosophy and the political situation of Poland from the 19th century to the post World War II era. This talk was delivered for international students enrolled in a course: Ancient Greek Democracy and Its Legacy taught in UHK by professor Jaroslav Daneš, with whom AΦR research group has successfully co-operated for many years.

The topics covered in this talk included a brief overview of how political situation of Poland changed and how various researchers of Plato interpreted his political ideas. The lecture started with Bolesław Limanowski (1835-1935), an advocate of socialism, who used Plato’s ideas as an evidence that socialism had been present in European thought from its very beginning. The next was Wojciech Dzieduszycki (1848-1909), a conservative politician, who ridiculed gender equality and socialism as political phantasies. Wincenty Lutosławski (1863-1954) considered totalitarian character of Plato’s polis as a natural consequence of his idealism, but after the World War II emphasised Plato’s evolution and his affinity to Christianity. Stefan Pawlicki (1839-1916), a Christian thinker rejected the connection between socialism and Plato, but praised the idea of preventive censorship. At the dawn of Polish independence after World War I Eugeniusz Jarra (1881-1973) welcomed the idea that social promotion or demotion in the state should depend on personal capabilities, and that the elites should no longer consist of the members of aristocracy but of the most gifted individuals. After World War II, in the Stalinist period, the criticism of Plato stemmed from various premises. Tadeusz Kroński (1907-1958), on the one hand, a Marxist thinker, considered Plato’s political philosophy as an aristocratic reaction to democratic changes in Athens, and in general as an expression of obscurantism and religiosity. Władysław Witwicki (1878-1948), on the other hand, was apparently critical towards Plato’s political project, assessing it as a monastery, concentration camp and a totalitarian state, but actually it was a criticism in disguise of the then political system.

In spite of the fact that the history of Poland or Polish philosophy was completely new for the members of the audience, their questions and remarks demonstrated that they were able to see the relations between the views of Plato’s interpreters and their interpretations of Plato’s Republic. Moreover, as usually, the discussion was the evidence that more general issues related to Plato’s legacy remain topical and stimulating as, for example, the chronology of Plato’s dialogues or reliability of image of Socrates.

History of Classics Discussed at UHK

An essential part of the Oral History and the Classics project was a conference held in the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Hradec Králové. This academic meeting which took place on June 1st-2nd and was titled Classics: the Past, the Present, and the Future. It gathered specialists reflecting on various issues related to the development of classical studies including history of ancient philosophy.

The head of the project and the conference was professor Jaroslav Daneš, with some help from Tomasz Mróz (University of Zielona Góra), a researcher in the project. Participants of the conference focused on historical developments of the classics, including their own experiences, “personal paths”, on recent problems, e.g. with teaching classics, and on the perspectives of future research in this area of studies.

Platonic Inspirations was the title of the session during which an AΦR member,T. Mróz, delivered his paper: Plato in post-war Poland. Continuities and novelty. His talk was devoted to three Polish Plato scholars, who survived the World War II and attempted to include their experience of war and the post-war political situation of Poland into their studies on ancient philosophy. They were, starting with the oldest: Wincenty Lutosławski (1863-1954), Stanisław Lisiecki (1872-1960), Władysław Witwicki (1878-1948). It is sufficient to mention that it was the Marxist interpretation of Plato that was pushed in Poland after the war by Polish Marxist philosophers (e.g. by T. Kroński) and in general works on philosophy translated from Russian. In these circumstances Lutosławski planned to published a volume on Plato presenting him as an intellectual and moral remedy for Europe, Witwicki, quite the opposite, blamed the philosopher for inventing totalitarianism, and Lisiecki turned from Plato to Aristotle, who was more acceptable then as a naturalist and a critic of Plato.

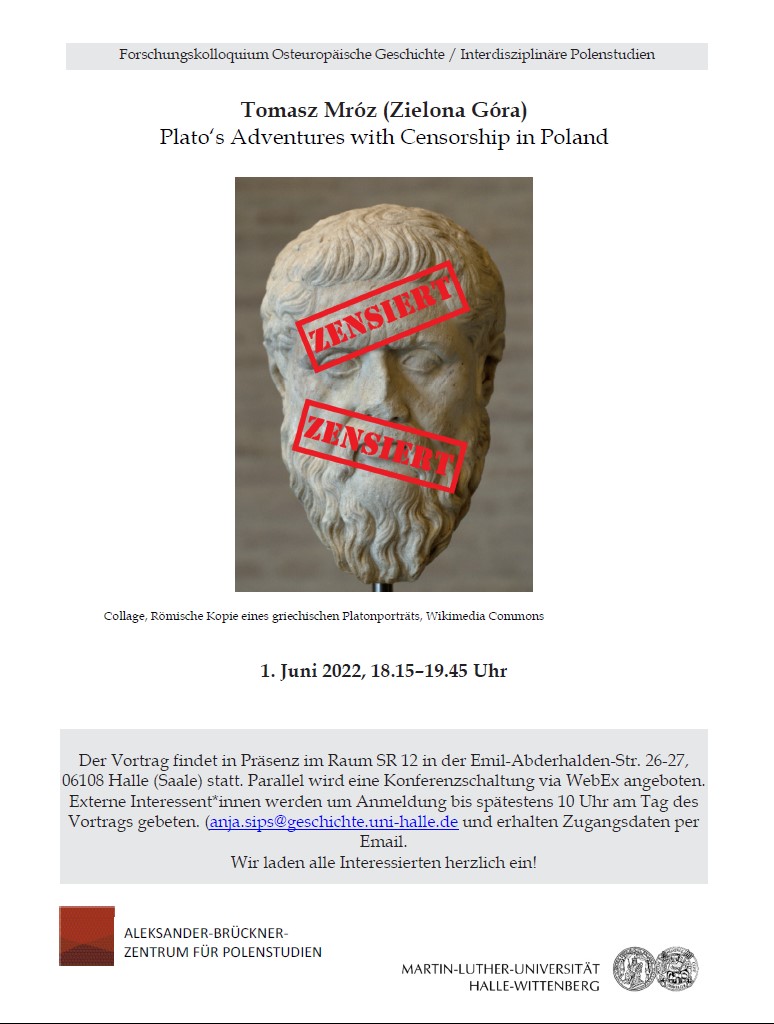

Plato’s Adventures with Censorship in Poland

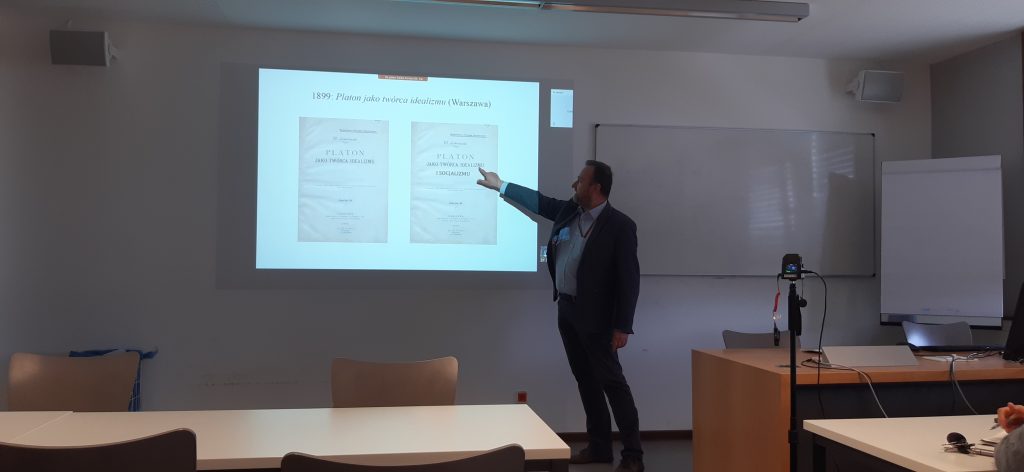

On June, 1st, a talk by Tomasz Mróz was delivered at the Interdisziplinäre Kolloquium Osteuropäische Geschichte / Polenstudien (Martin-Luther-Universität Halle). The topic of the presentation was the interference of various types of (broadly understood) censorship with Plato scholars and research on Plato in Poland. T. Mróz discussed three (and a half) cases of such interference. The talk was a supplemented and developed version of one of Mróz’s previous papers.

The first case of censorship was relatively harmless, for only one word, namely: socialism, was removed from the title of Wincenty Lutosławski’s book, Plato as a Creator of Idealism [and Socialism], (Warsaw 1899). Imperial Russian authorities in Warsaw removed the word “socialism” from the title and from the table of contents, without even looking into the text of his book on Plato, for “socialism” occurs on many pages, being – in Lutosławski’s view, a natural consequence of idealism.

Stanisław Lisiecki represented another case of broadly understood censorship. He was an enthusiast of Plato and a translator of his dialogues, but only his Republic saw the light of day in the interwar period, while all the remaining dialogues were left unpublished in the manuscripts. His leaving the clergy and Roman Catholic church was the most probable the reason of his difficult situation in Polish academia, for some scholars were unable to accept him as a colleague and assess his works without religious prejudice. As a result, his works were not published, but some justice in this regard has been recently done by the members of the AΦR research group.

Władysław Witwicki was more succesful in his translations of Plato’s works. Soon after the Word War II he managed to publish a small book on Plato (Plato as an Educationalist, 1947) and a translation of Plato’s Republic (1948). In the book and in his commentaries to Plato’s text, he compared the post-war reality of Poland and Plato’s political project to a concentration camp, great monastery, or a totalitarian state. Some of his remarks were censored and the second edition of the Republic (1958) appeared in print in an ideologically “corrected” version.

As the additional “half” of the censorship cases, Witwicki’s struggle with his sister, who was a Catholic nun, were presented. She tried to convince him not to criticize Catholicism in his commentaries, but he replied to her with a short comic story depicting his and Plato’s imaginary meeting with her, and Plato’s escape from holy water.

Thanks to the fact that the audience consisted of specialists in East-European history, in philosophy and in the historiography of philosophy, a wide spectrum of questions appeared and the author did his best to satisfy multi-oriented demands of the public.

T. Mróz’s stay in Halle was sponsored by Aleksander-Brückner-Zentrum für Polenstudien from the funds of Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD).

Censorship against Plato Scholars and Plato Himself

A volume on various aspects of relations between censorship, politics and oppression was published in 2018 by Gdańsk University Press. The book was a result of an international conference which took place in Gdańsk in 2017.

A paper by T. Mróz, included in this collective volume, discusses three cases of censorship on works of Polish Plato scholars who were active in three various periods of Polish history. First, the title of W. Lutosławski’s book on Plato was shortened by Imperial Russian authorities in Warsaw, they removed the word “socialism” from the title of his book on Plato. Its final version was then reduced to “Plato as the Creator of Idealism”.

S. Lisiecki, in turn, translated dialogues and wrote extensive introductions to them, but only his Republic saw the light of day in the interwar period, while all the remaining dialogues were left unpublished (but some of them, fortunately, will be published this year!). His leaving the clergy and Roman Catholic church might have been one of the reasons of his difficult situation in Polish academia.

Finally, W. Witwicki’s translation of the Republic with his commentaries appeared in print in 1948. After his death, the second edition was published in 1958, but some of his ironic and critical remarks on totalitarian system were removed.

Paper by T. Mróz can be downloaded from the University’s repository here.

Recent commentaries